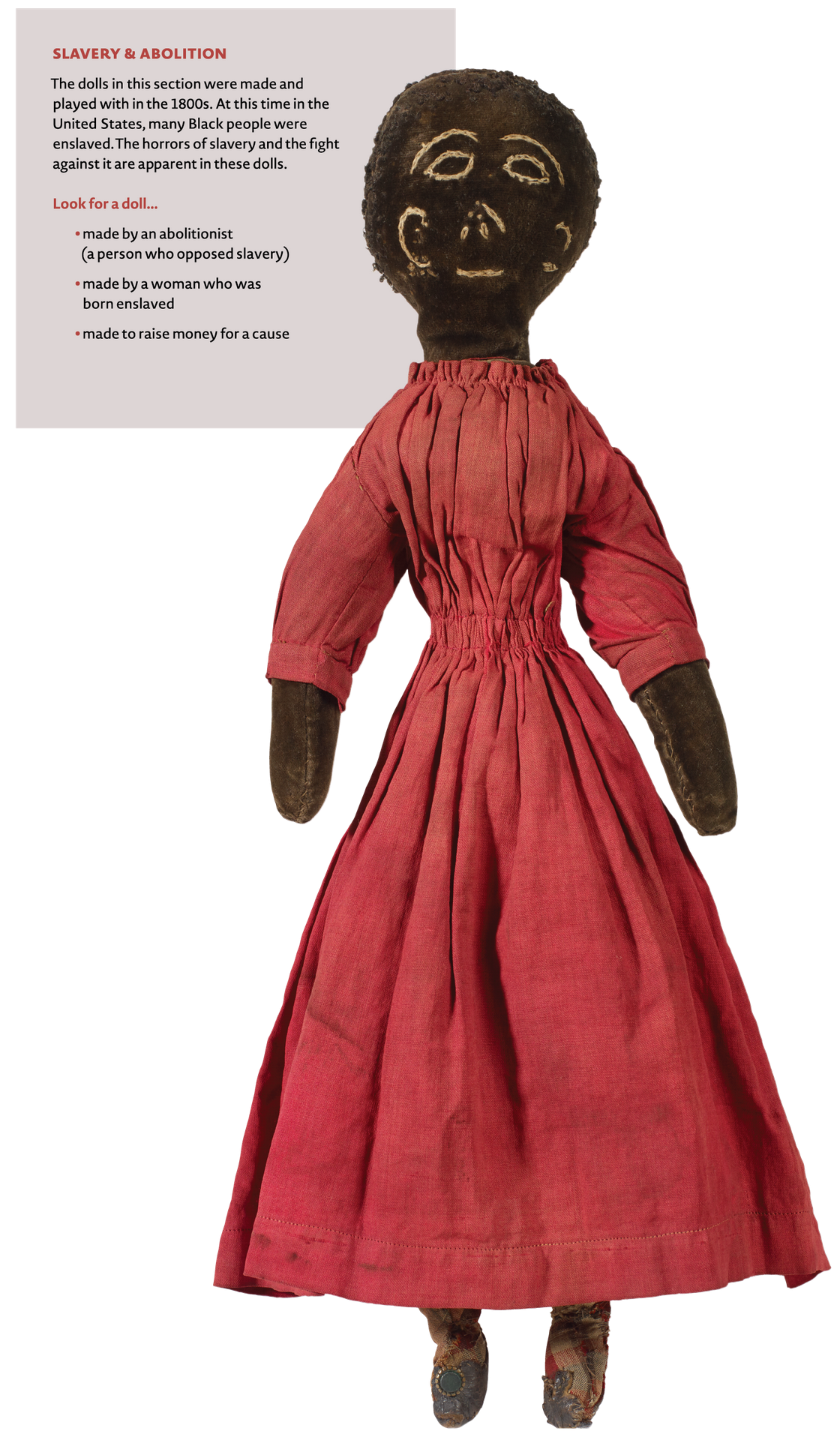

Enslaved people made and played with some of the

earliest Black dolls in America. Oral histories and the few surviving dolls

provide evidence that enslaved children played with and cherished “rag dolls.”

The frequent mention of cloth dolls is not surprising, given that many enslaved

artisans spun, knitted, wove, and stitched bedding and clothing for their

owners. Enslaved people also made cloth goods for

their own homes, families, and communities. Skilled seamstress Harriet Jacobs,

for instance, was charged with sewing clothes for the other enslaved people on

a family plantation and later used her needle to make dolls for the children in

her care.

Prior to emancipation, Black and white women alike

took up the needle as a political tool. The act of making dolls for

enslaved children affirmed their personhood and right to play when the slave

system denied their very humanity. Northern women organized fairs to raise money for the

abolitionist cause in the 1830s through the 1850s.

Antislavery sewing circles

made up of women and children contributed clothes, dolls, and household items.

At these fairs, the price tags attached to Black dolls underscored the evils of

a system that condoned sale and ownership of human lives.

Doll

in gentleman’s top coat,

Milton, MA, ca. 1860-70

Mixed fabrics, leather, brass, glass

A handwritten note accompanying this doll states that

it was stitched by a member of the Badger family of Milton, Massachusetts, and

sold to support Union soldiers during the Civil War.

This dignified gentleman defies racist stereotypes,

perhaps a goal of doll makers for antislavery and Civil War era fundraising

fairs. Some abolitionist families encouraged their children to play with dolls

like this to help instill humanitarian values.

Cynthia Walker Hill (1771-1848)

Doll representing an enslaved man,

ca.1840-48

Cotton, silk, glass, wire, pearl

New Bedford Whaling Museum,

Gift of Mrs. M. Motley

Sargeant, 1953.1.

2

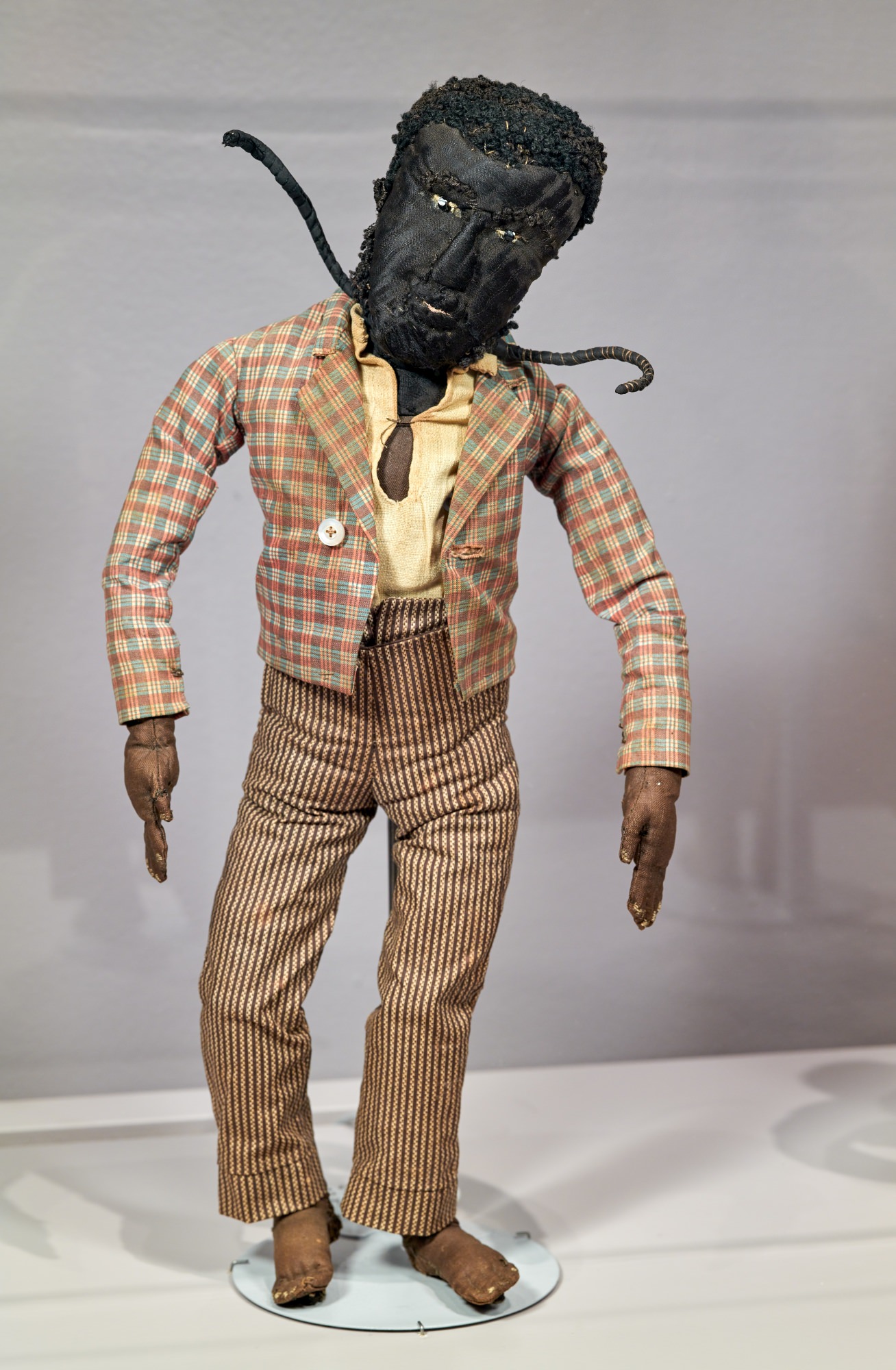

The horrors of slavery are palpable in this doll, a

fugitive from slavery wearing a three-pronged slave collar around his neck.

The doll was made by Cynthia Hill, a fervent

abolitionist from Providence, Rhode Island. A hotbed of abolitionist activity,

Providence was one of many New England towns that formed antislavery societies

in the 1830s.

Cynthia Walker Hill (1771-1848)

Doll representing Frederick Douglass,

ca. 1840-48

Cotton, silk, glass, porcelain

New Bedford Whaling Museum, Gift of Mrs. M. Motley

Sargeant, 1953.1.1

Born into slavery, the abolitionist Frederick Douglass escaped to the North and settled with his wife in the abolitionist stronghold of New Bedford, Massachusetts. In 1841, he began giving lectures about his struggle for freedom and urging others to join the fight against slavery. Providence abolitionist Cynthia Hill, perhaps inspired by an eloquent speech or his compelling autobiography, created this doll in Douglass’s image to honor him and his struggle for abolition.

Rosena Disery (1805-1877)

Sampler stitched at the New York

African

Free School, 1820

Silk on linen

New-York Historical Society, Purchased

through the generosity of the Monsky family, the Coby Foundation, Barbara

Knowles Debs and Richard A. Debs, Patricia D. Klingenstein, Nancy Newcomb and

John Hargraves, Charles Phillips, Pam B. Schafler, Sue Ann Weinberg, and the

Goins Family Fund, 2011.9

Sewing was a valuable skill for free

Black women and girls. At the New York African Free School—founded in 1787 to

educate and aid Black children—all female students learned to sew.

Fifteen-year-old student Rosena Disery stitched this spare sampler as a school

exercise and displayed it as evidence of her needlework prowess. By the time

she graduated, Rosena would have learned plain sewing, mending, knitting, and basic

embroidery: all useful skills for making dolls.

Sarah Ricks (b. 1835)

Sampler stitched at Colored Public School No. 3,

Williamsburg, Brooklyn,

ca. 1845-50

Wool and silk on linen,

New-York Historical Society Purchase, 2012.11

Sarah Ricks, daughter of a prominent Black

abolitionist, made this sampler while attending Brooklyn’s Colored Public

School No. 3. Embroidering the alphabet in simple cross-stitch started Sarah on

the path to mastering sewing, a skill she might eventually use to help support

a family.

Harriet Jacobs (1813-1897), Dolls made for the Willis family children, ca. 1850-60. Mixed fabrics, metal. Private Collection

Harriet Jacobs (1813-1897)

Incidents in the Life of a

Slave Girl.

Boston, 1862

Harriet Jacobs wrote her autobiography during the

1850s while caring for the Willis children. She finally published it in 1861

under the pseudonym Linda Brent, with editorial help from antislavery author

Lydia Maria Child. Until the 1980s, most readers assumed that Child had written

the book. Today Jacobs’s authorship is unquestioned, and her work is considered

one of the most important slave narratives ever written.

Jacobs recounts her desperate flight from slavery,

spurred by the violence and sexual predation of her owner. She hid in an attic

crawl space for nearly seven years before managing to escape to the North and

eventually reunite with her children. In that gloomy garrett, Jacobs sewed to

relieve her loneliness.