Until

the early 1900s, most Black dolls in the U.S. were handmade. European companies

manufactured the first white baby dolls in the mid-19th century and produced

Black baby dolls soon thereafter. Importation of these high-end bisque examples

was costly, however. Black reformers and parents came up with a solution: commercially-available Black dolls that

countered the effects of segregation and empowered Black children by

celebrating their features.

In

the last 70 years, people have created new meanings for Black dolls. Lawyers

brought research on racial doll preferences before the Supreme Court.

Large-scale manufacturers created Black dolls to encourage conversation around

slavery as well as contemporary standards of beauty with children. Today, Black

doll collectors continue to forge communities, in person and online, to

celebrate their shared interest.

Handmade

or commercially produced, Black dolls remain both a beloved source of play and

a key tool in teaching children about race.

In

1954, NAACP lawyer Thurgood Marshall argued against racially segregated schools

before the Supreme Court. He asked Black sociologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark

to submit testimony for Brown v. Board of

Education. Beginning with Mamie Clark's master’s thesis, the Clarks had

spent decades researching race consciousness in Black children.

Kenneth

Clark spoke broadly about their work, including the famous doll test. The

Clarks used dolls like these, identical except for skin color. They asked

children to compare them: “Which is the doll that looks like you?” “Which is

the good doll?” They found that Black children preferred the white doll.

Marshall

argued that the Clarks’ research proved racial segregation harmed Black

children and produced feelings of inferiority. The Supreme Court cited the test

as particularly influential in their decision. They ultimately ruled that

schools integrate “with all deliberate speed.”

Effanbee Toy Company Twinkie dolls, ca. 1968. Vinyl, textile. Private collection of Debbie Garrett

Gordon Parks (1912-2006), Untitled, Harlem, New York, 1947. Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation

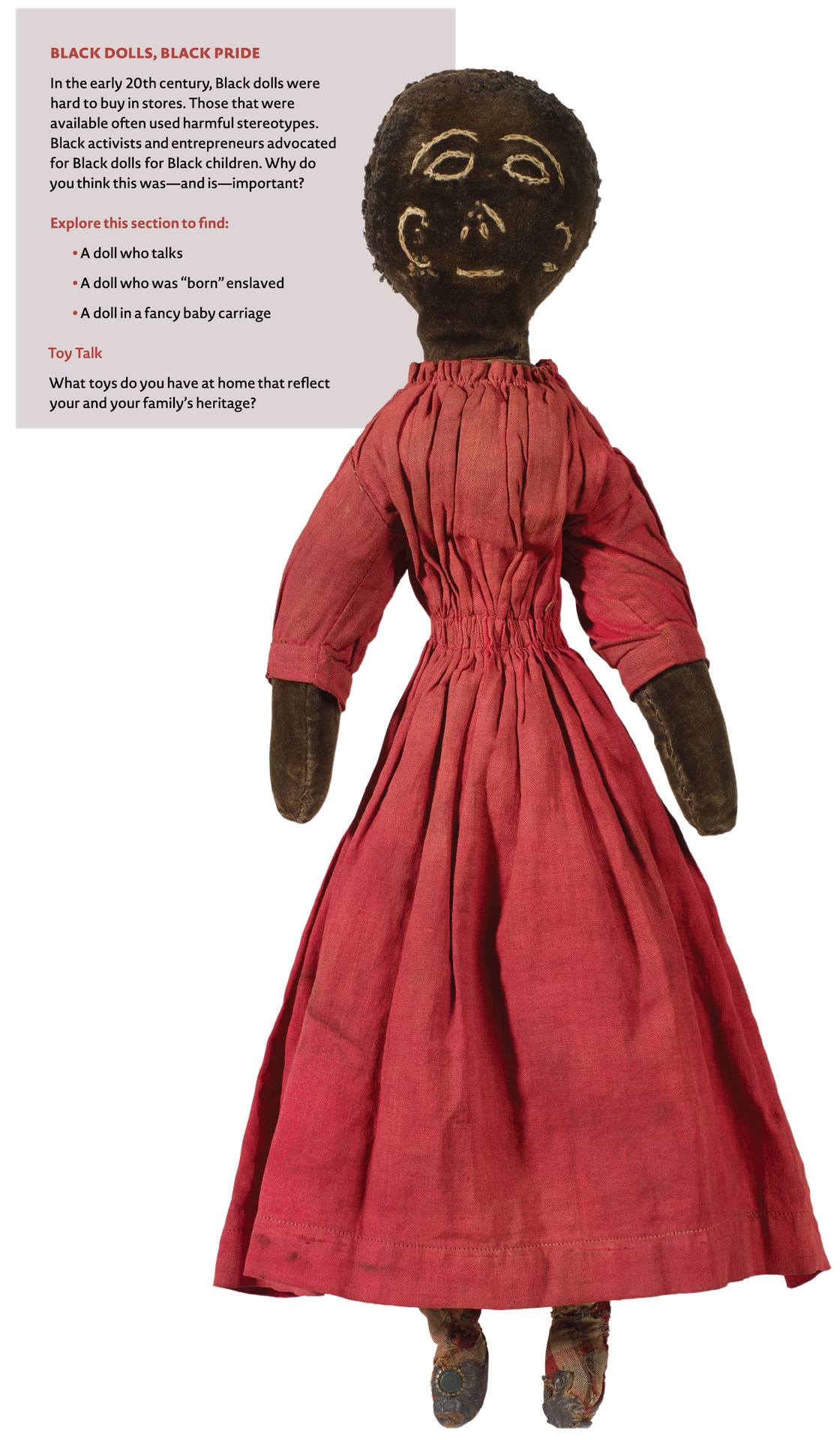

In

the early 20th century, many commercially available Black dolls reflected

derogatory stereotypes. The National Negro Doll Company became the first

American firm to retail Black dolls with a positive image in 1908. Founder

Richard Henry Boyd first sold imported dolls like this German example, but by

1911, he began manufacturing them, promoted with the slogan “Negro Dolls for

Negro Children.”

In

1918, Harlem businesswomen Evelyn Berry and Victoria Ross started a similar

venture to manufacture Black dolls. The Universal Negro Improvement Association,

founded by Marcus Garvey, bought the company, declaring that Black children

needed "dolls that look

like them to play with and cuddle.” They were among a number of

retailers who marketed their products through eye-catching advertisements that

aligned their products with Black middle-class uplift and social mobility.

Shindana

Toys

Baby

Nancy doll,

ca. 1968

Vinyl,

mixed fabrics

New-York

Historical Society

Following

the deadly 1968 uprising in the Watts area of Los Angeles, local Black

residents came together to create Shindana Toys, a company designed to uplift

the struggling neighborhood and create jobs. Shindana’s first doll, Baby Nancy,

celebrated Black hair and features, and sported clothes designed and sewn by

local Black women. Baby Nancy quickly became the best-selling doll in Los

Angeles, and within months was in high demand nationwide.

Pleasant

Company

Addy

Walker doll, family album quilt, Meet

Addy book, Ida Bean doll,

ca. 1993

Plastic,

mixed fabrics

New-York

Historical Society, Gift of Nicole Wagner & Wagner family, 2019.32; Quilt, Courtesy of

Emily Schulman, PhD

In

1993, after initial success with their American Girl line of dolls that

incorporated stories from American history, the Pleasant Company launched its

first Black character, Addy Walker, to tell the story of American slavery and

emancipation. Scholars of African American history contributed their insights

to develop a powerful narrative of the horrors of slavery and the triumphant

perseverance of Black families.

Addy’s

braided hair and West African cowrie shell necklace are memorable markers of

Black culture, and her quilt was modeled on an 1854 family album quilt by Black

quilter Sarah Ann Wilson. Addy even came with her own cloth doll, Ida Bean.